In the renaissance of water sports, South African Corran Addison has touched all aspects. A canoeist and kayaker, a surfer and surfboard and kayak designer, he been at the foremost of paddling innovation. An Olympian in the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona, Addison competed for South Africa in a number of world freestyle kayaking championships, winning more events than any other competitor in the years 1993 to 1999. In 1987, Addison successfully ran 101-foot vertical drop into Lake Tignes in France at the time one of the highest waterfall kayaking attempts ever made.

Addison has not only made his mark as a competitor but a designer as well while working for Perception Kayaks, Riot Kayaks, and Dragorossi. He is credited with the developing the planing-hull kayak a technology used in most modern whitewater kayaks. In 2003 he moved on with an interest in surfing and stand up paddle boards in both a competitive and design. He formed Corran SUP in 2012 and sold the brand to Kayak Distribution in January 2015.

Innovated and always controversial, Addison gives us his keen insight into the world of whitewater paddling in both SUPs and kayaking from where it all began and its bright future.

NC: You’ve been on the scene for a long time now and have seen a lot of revolutions. How has water sports, SUPs and kayaking changed in your lifetime?

CA: It has changed a lot in my life-time because of where I learned to kayak, in South Africa in the 1970s. South Africa was completely detached from the rest of the world because of Apartheid sanctions against the country. So when I started to kayak it wasn't like in the US, where you walk into a store and you could buy a life jacket, spray skirt, helmet, paddle and a boat and go paddling. I mean by the 1970s there were plastic boats in production in both the United States and Canada. By 1972 there were two companies making mass-produced plastic boats and before then you could still go and buy a fiberglass boat from any one of a dozen manufacturers in the United States and two to three dozen manufacturers in Europe who were producing fiberglass Kevlar kayaks.

So we had to design either a boat or find a mold somewhere and just figure out ourselves how to produce them. So the boats we were paddling were very rudimentary. We didn't even know about the Eskimo roll, didn't know what a brace was and didn't have spray skirts. We didn't know about spray skirts. That came years later. After we started kayaking, we figured out to cover up the cockpit and made paddles out of plywood and closet dowels. So in my lifetime kayaking has changed enormously from that to what kayaking is today.

But you could say that essentially if you took my commercial lifetime, my modern lifetime, when I started paddling in the United States and working for Perception in 1988, from then to now: Even in that almost 30 year period of time kayaking has changed. In many ways, it changed significantly and in some ways, it hasn't changed that much. If you consider the Perception Dancer as an example, by 1988-89 it was linear shell instead of a cross-linked shell with cockpit thigh brace seat, foot braces and center bracing in the boat. It didn't have a back band and the cockpit was small, but, it had safe grab loops that you could tie into in case of a pin. We had neoprene spray skirts and fiberglass and carbon paddles and things like this, so here again kayaking was relatively advanced.

In another sense, we haven't really moved forward that far either. If you look at the latest kayaks that are on the market they are still a rotomolded polyethylene with your basic seat, thigh brace and foot brace in the boats. The outfits have gotten a little fancier, it all moves around a little bit easier and you have to spend less time with glue and foam getting your boat fit. But, in many ways, the technology that we’re using to manufacture a kayak in 2016 is almost identical to the technology of 1988. That is pretty sad when you think about it. We haven't in thirty years come up with a better way of making a kayak.

On the flip side, you look at what boating was in the late 1980s in the United States anyway. An overflowing creek in the Southeast was considered the epiphany of what was possible to run. It was steep. It was shallow. It was rocky and people were getting pinned in there in their pointy low rocker small cockpit Dancers. The understanding of how to boof was still very limited. You paddled up to a drop as fast as you could and hope that your nose came up and you didn't hit something on the way down. And you look at what the kids are doing today, wherein 1988 if you were running a 20-foot waterfall you were something special. Today, guys are doing 8 or 9 loops in an afternoon over 50-footers. They will go to a 50-footer and run it a dozen times and run successfully. There is no luck involved. It is exact and it's precise. So technically what we are doing with kayaks has come along way, even if the technology of how we are making kayaks really hasn't changed much.

Rodeo or freestyling in the late 1980s was side surfing a hole and doing flat spins on the corners with some paddle twirls, eating a banana and juggling. By the mid to late 1980s, you had the guys on the west coast who were starting to figure out rolls and vertical moves, into staying in the hole or wingover as they called it. By about 1991, the first cartwheels were becoming relatively commonplace. In 1993 there fewer than 30 to 40 people in the world who were linking 15 ends in a row in cartwheeling and split wheeling and everything else. And you look at the aerial stuff that has come along in the late 90s and how it has exploded in the 2000s, being combined into multiple axis rotations and at the same time going six to seven feet in the air. It has come a long way.

NC: What big changes do you see on the horizon: are boards going to bigger or smaller in the future?

CA: Like anything form follows function. The surf shapes are getting smaller and smaller. The board that I surf on I can barely stand on. My ankles are on the water level. So the whole board is underwater which means that I'm paddling a board which has negative floatation for my weight. But it's a park and play. I can paddle out into the eddy line out on to the wave, but that's about it. I'm not going anywhere on that.

At the same time, the creek boards or boards for running rivers are getting bigger and in that sense, they are getting wider. They are getting shorter. They started around ten feet in about 2008, but the one I'm on now is 8 ½ feet long and went from 32 to 33 inches wide to about 35 to 36 inches wide.

For your average hardcore river running, creek boating, whitewater SUP slalom or boardercross: the tops are narrower, probably closer to 30 inches and they are about 10 1/2-feet long, which is an unspoken rule that most of the events. Someone came up with 10 1/2-feet and that where it stuck.

So it hard to say if they are going to get bigger or smaller. Form does follow function and it depends on what we are doing with them. But it going to interesting to see.

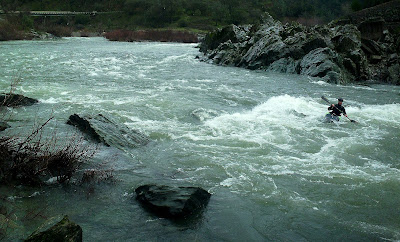

NC: You recently teamed up with Waterlust filmmaker Patrick Rynne, ripping up the river while paddling a SUP. Tell us about that experience?

CA: It was an interesting experience. We didn't run anything particularly hard. It was all relatively easy stuff that we were running. But it was great to work with a film crew who were absolutely on the ball. These guys didn't mess around. They were willing to put their several thousands of dollars worth of camera equipment in jeopardy. I almost knocked what they call the squirrel cam into the water a number of times when they got so close to me. I actually hit it with my paddle and almost knocked it into the water, and that would have been the end of that. They took their time to set some stuff up, which means lots of time sitting around waiting for stuff to happen. But their footage was fantastic.

So it was a real pleasure to work with those guys. Dan Devio is always such a pleasure to paddle with. He is really one of the better paddlers out there. I have paddled with him now for 30 years, and we have a great relationship when we paddle together. We just know what seems to be working and there is a lot of nonverbal communication that goes on. So I always enjoy paddling with him. So overall it was a great experience. I hope to do more like it, possibly with the Waterlust crew or other crews like it.

NC: So is there a future in SUPs and whitewater?

CA: I think absolutely yes! I'm speaking to the older crowd of kayakers if you live somewhere, where there is Class III or II section of river that is near your house and you have run this thing a 1000 times. You reach a point to where you're no longer getting any better and you don't paddle often enough anymore. The kids are all getting better and better, and you have just sort of been stagnating or even possibly getting worse than you once were due to life commitments and things like that. Age and achy bones and sore muscles.

And what SUP does is offers a challenge and that sensation and newness. That feeling of getting better every time you go, that was so attractive about kayaking when these people first started. You remember back when you first learned to kayak and every time you went out, you were better when you got home than when you when you left at the beginning of that day. There was this feeling of progression that was exciting and addicting.

And what SUP does is it brings that to people without having to throw in the element of death. In other words, you don't have to challenge yourself in Class V whitewater in order to feel like you're challenging yourself and moving forward. And that is a huge draw for people.

It's also generally cheaper than kayaks. It's nice to be able to go out and buy a new toy and it's not cost you a thousand, two thousand or three thousand dollars, so that is very attractive. I think there is a massive draw towards it and we are seeing it definitely in sales. It is arguably easier to sell a couple hundred whitewater paddle boards than a couple hundred kayaks. Now there is less competition of course, and that's a big part of it.

But, also I think now we're going to see some of the youth interested. This last year, I ran a section of the Rouge River of the Seven Sisters which is in notorious for giving people some beat downs. It's not super challenging Class V, but there is some potential for beat downs, there’s some potential for some pain and some hold downs and some swims. The World Class Academy, this massive group of kids, were there kayaking these drops and having a good time. I just happen to be there at the same time with my SUP running some drops. And it was an eye-opener! A number of these kids came up to me afterward and say, 'This was the first time they had ever seen a SUP that was legitimate.' There wasn't somebody just wobbling their way down a class II rapid trying desperately not to fall in, half the time on their knees or in a low brace, hunched over like an old man. I was running legitimate rapids and I was sticking some of them, not all them.

NC: What hasn't changed about water sports that keeps bringing you back?

CA: Mountains, rivers, movements. I love my time in California, I spent 5 years living at the beach in California surfing every day. But when you're surfing you drive to where you are going to be. For the most part, you paddle out and you stay there for the whole session. You can paddle up and down the coast, but you generally have to do that on a bigger board and when you get to a break, your board is too big to be any fun. So generally speaking if you're a high-performance surfer you drive where you want to go, and if you do a 3-hour session,

three hours later the view is like exactly the same as it was when you started. It never changes. I missed the feeling of getting on a river and going downstream, watching the banks pass by, seeing the mountains come by; that feeling of adventure you have from the movement of going somewhere. So while in California I was making these long drives to places to go paddling, either SUP or kayak and I realized that it would be much easier if I just moved somewhere where the kayaking is great. Kayaking is always good to me here in Montreal, Canada so that is why I moved here as a base. Already in the last few months, I've done more paddling than I did in the last 5 years. So I'm very excited.

NC: You have made this your life's work. Anything you are most proud of? How much has that made an impact on the sport?

CA: You know it hasn't always felt like work. That is the nice thing about what I have managed to do with my life. A lot of it has been fun. I look back on the days when I was with Riot and the team over there and the fun that we had. And when I moved on Draggo, I spent a lot of time in Italy, learned the language, made a lot of friends over there and spent a lot of time paddling in Europe. It was really exciting and fun.

So it hasn't really been work. Even though sometimes you have to work. You have to grind fiberglass and which is not particularly exciting. You have to get on the phone and call dealers and make sales. But it's a small part of it. The fun part is developing and prototyping new ideas and building these things. Going out and using the products and seeing the excitement on other people's faces when they try something you've done or you have built, and how much pleasure it brings them to be in a boat or on a board or something that you came up with, that has changed their life, that is very rewarding.

What I'm most proud of? The Olympic Games, it's hard to beat that. On the professional level, I mastered the concept of the planing hull for a whitewater kayak or freestyle kayak. If you look at what kayaking was before the first one that I did - the Fury - and what people were doing in kayaks within one year of having it (the first successful planing hulled boat) developed, The Fury did really change the sport. All of the boats that you see on the market today are loosely based on the base concepts that I came up with for the Fury. Obviously, design concepts have evolved. If you went back and got in a Fury today, you’d probably think it was a piece of shit, compared to what is on the market today. But the boats that are on the market today wouldn't be here if it hadn't been for that boat.

You wouldn't have people doing bread and butter if we hadn't come up with the blunt and the air blunt. So these were critical things. Many people are doing the moves that I either invented or spins offs of the moves I started; I came up with most of the aerial moves and spin style moves that are done in a kayak today. And even the ones that I didn't come up with came from the ones I did come up with.

So it is great to see where kayaking is and know that I had a massive part to play. There were other people involved of course, but I had my part to play in it, it was a fairly sizable part, and it's nice to look back on it and say "WOW!" I look at the sport today and I'm in a large way responsible for where it is today, and it's a really good feeling.

The kids today that are creeking or freestyle are at a level which is vastly superior to anything that I ever was, even in my prime. But, that's the nature of things. Sports move forward. The new generation is always better than the old generation. But, it's still fun to see that what they are doing came from what we came up with.

This Q/A with Corran Addison was originally published in Dirt Bag Paddlers and DBP MAGAZINE ONLINE.